If you'd rather get this information in video form, click here. If not, keep reading below.

Powerlifting meet day attempt selection is actually pretty clear-cut once you understand it. It can be broken down to a science, following exact percentage ranges. This turns it into a repeatable process based on numbers rather than guesswork or “feel.” If you’re outside these percentage ranges, you’re likely leaving kilos on the platform or putting yourself at risk of bombing out.

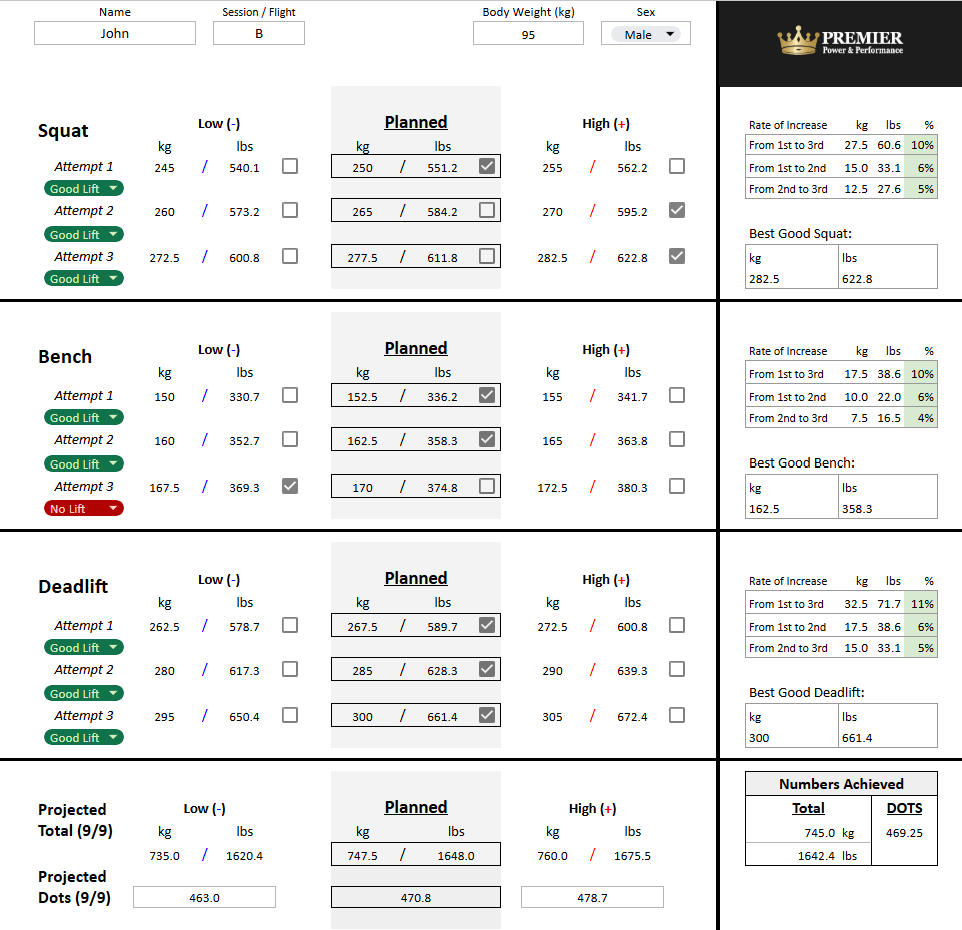

In this article, you’ll learn how to plan your opener, second, and third attempts using these percentage ranges so you can consistently have great meet performances. I’ll also walk you through the exact framework I use with my athletes, and if you’d like, you can download a free copy of my attempt planner (Google Sheet) to simplify the entire process.

I was the assistant coach for Team USA at the IPL Powerlifting World Championships in 2023 and 2024, and these are the same percentages we used to plan attempts for our athletes - helping us win best team/country as well as best overall male and female lifters both years. The attempt planner linked at the end of this article is the same one I built for our coaching staff to use to simplify the process of planning and tracking attempts for 24 athletes over 4 days. Its many built-in functions should help make your planning easier too, whether you’re a first-time competitor planning your own meet or a coach managing multiple lifters across a long meet weekend.

Your Third Attempt

The percentages used to plan your attempts are based on a realistic planned third attempt, so we're going to start there.

Your third attempt should be a small margin more than the heaviest lift you hit in training leading up to the meet. This is because generally you don't need to hit an absolute max in the gym prior to meet day (just something fairly heavy, like a single at RPE 9), whereas on meet day it is fine to aim for the biggest number you can hit. Plus, you should be a little stronger on meet day after tapering and dropping some fatigue.

Don’t let magical thinking creep in, though. You will not miraculously be way stronger on meet day. If you artificially inflate your planned third attempt, all you’re doing is making your opener and second harder than they need to be and increasing the chance you'll miss your third.

A realistic expectation is that you may be able to add about 3% more than you hit in training. However, if your last heavy lift in training was a really tough grind or not fully to competition standards, or if you are cutting weight for the meet, then you may want to be a bit more conservative. You may even aim to just match your best lift from training without adding anything extra to it.

Recommended Percentages

Once you have your planned third attempt, we are going to base the other numbers on this as follows...

Opener:

87-91% of your planned third. (This also aligns pretty closely with the age-old powerlifting advice that you should open with a weight that you can hit for a triple.)

Second attempt:

94-96% of your planned third, meaning you jumped up about 5-8% from your opener.

Third attempt:

The planned 100%. This is a jump of about 4-6% from your second.

You’ll notice the jump from the first to second attempt is slightly larger than the jump from the second to third. This is intentional. A conservative opener ensures you’re on the board no matter how the day is going, even if you’re sick, nervous, or slept poorly.

The smaller jump from second to third makes your top attempt more predictable. Strength can fluctuate day to day, so taking roughly 95% on your second attempt gives you a clear picture of what you’re capable of on that day. From there, you can confidently select a third attempt that pushes your limits without overshooting and missing.

Want to make this even easier? Grab the free Attempt Planner (Google Sheet) I use with my athletes — as you enter the numbers you are thinking of for your opener, second, and third attempt, it calculates the rate of increase percentages automatically so you can focus on lifting, not math.

Exception: Lower Max Lifters

Generally the only time I would deviate from these percentage ranges is if you have a lower one rep max, such as ~50 kg or less. For example, if someone went 45/50/52.5 kg (100/110/115 lbs) for their three attempts, that is 14.3% difference from 1st-3rd attempt, 9.5% from 1st-2nd, and 4.7% from 2nd-3rd. While this is slightly above the recommended ranges, this is still a reasonable attempt plan. You are only jumping 5 then 2.5 kg, which is totally fine. The percentages are just more heavily skewed by the jumps (which have to be in increments of 2.5 kg) the lower the one rep max is. Anything over a max of about 75-100 kg shouldn't have to worry about this and should be within the recommended ranges.

Outside of this one exception, the percentages and jumps are a fairly hard rule, not just a loose suggestion. You should follow them if you're looking to optimize performance. That is because if you go far outside these ranges, your jumps are either too large or too small, each of which has downsides that I'll explain below.

Too Small Jumps

The problem with making too small jumps between attempts is that you are wasting energy. Think about it like this - if you were trying to hit a one rep max in the gym, how would you go about it? Would you take two really heavy lifts right before it or not? No, you would take decent size jumps from your last warmup to the top set of the day. The same should be true on meet day from your first to second, and second to third. This saves energy and lets you hit the biggest third attempt you can.

Your opener should basically be like your last warmup, but done on the platform. Then the second attempt is moderately hard, and the third is challenging.

Where most people go wrong is they want to take all of their attempts hard and heavy, but that isn't realistic. If you open heavier than needed, you are fatiguing yourself and limiting what you could do on your third. Think about it like this, we want to start cool and finish hot, otherwise all three will just end up lukewarm.

Too Large Jumps

There are two main problems with making jumps that are too big.

First, you will probably not be as prepared for the next weight. It’s no different than skipping a warmup set in the gym - it would be a bit of a shock to your body. It would feel extra heavy and less well grooved. The same thing can happen on the platform when you make massive jumps between attempts. Each lift should serve as a stepping stone, setting you up for the third attempt.

Second, large jumps magnify the consequences of a missed lift. While failed attempts should be rare if you’re planning correctly, they do happen. When they do, bigger jumps mean a larger hit to your total. Reasonable jumps strike a balance between conserving energy and limiting the downside if something goes wrong, which is why we don’t default to always making tiny, conservative 2.5 kg increases.

What About Warmups?

Generally I like people's last warmup to be below their opener weight by the same size jump we're expecting to make from the 1st to 2nd attempt. For example, if we are planning on going 250/265/277.5 kg, that is a 15 kg jump 1st-2nd. I would match that size jump to the opener and take about 235 kg as their last warmup. Sometimes I may drop it down by 2.5 to 5 kg less to save a little more energy, particularly if we're over 200 kg. But, just like we talked about with the attempts, we don't want that jump getting either too big or too small from the last warmup to the opener or it causes the same issues.

All of the warmups prior to the last one are a little less important in terms of the exact weight, since they won't be as heavy and shouldn't be too fatiguing. I would just aim for 4-6 warmups in total (since on meet day you are sharing equipment to warm up with and may not have a lot of time). Disperse these warmups in reasonable sized jumps, building up to the last warmup weight.

You should take your last warmup about 10 minutes or 10 lifters before your first attempt. This gives you a good bit of rest afterwards, before you are up for your opener, but not so much that you start to get cold. If you're the first lifter in the first flight, then this would be 10 minutes before start time or before the break between squat/bench and bench/deadlift ends. If you aren't, then you factor in a minute per lifter before you, both within your flight and the flight before yours. For example, if you are the 8th lifter in flight C, you should aim to take your last warmup when there's two lifters left in flight B.

Flexibility of Plan

There's one last thing to plan. Like we said earlier, strength can fluctuate day to day, so we want to be ready for this. If you're having a great meet, we can push a little extra. If you're having a bad meet, we want to be able to pull back. This is easier when you have a pre-planned high and low range. To do that, take your planned first, second, and third attempt and add 2% for the high side, and subtract 2% for the low side. (Or you can use the Attempt Planner tool below and it will automatically generate the high and low ranges for you as you enter your planned attempts.)

Then, on meet day, be willing to call either the low, planned, or high numbers based on how the previous attempt felt and looked.

Attempt Planner Tool

If you want to apply everything in this article without doing all the math by hand, you can download the same attempt planner I use with my athletes. As you enter your planned attempts, it automatically calculates the rate of increase, and the color coding lets you know if it is reasonable. If it is green, you're good to go. If it is orange or red, you are outside the recommended ranges and may want to tweak the numbers.

The sheet also generates the high and low values based on your planned attempts. Plus you can use it during the meet to track what weights you've hit, so that it calculates your current total and DOTS score. This helps keep decision-making simple when time is short and stress is high.

Whether you’re a first-time competitor planning your own attempts or a coach managing multiple lifters across a long meet weekend, this tool gives you a clear, repeatable system for meet day success.

Download the free Attempt Planner here:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1PY67ejT3PZg0ObvoXQljNNhumFnrO9EFf__4GisdvF4/edit?usp=sharing

Hope this helps!

Best,

Michael Elrod-Erickson

Founder and Head Coach, Premier Power & Performance

P.S. - If you found this useful and you’d like to get notified when I publish more articles and resources, you can click here to join the Premier newsletter.